The Egyptian Empire: Rise, Golden Age, and Legacy

This in-depth exploration examines one of history's most remarkable civilizations, spanning over three millennia from 3100 BCE to 30 BCE. From the architectural marvels of the pyramids to groundbreaking advancements in science and medicine, discover how ancient Egypt shaped human history and continues to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts alike. This comprehensive article delves into the political systems, religious beliefs, cultural achievements, and daily life of a civilization that maintained remarkable continuity while creating innovations that would influence the ancient world and beyond.

EMPIRES/HISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGEHISTORY

Keshav Jha / Kim Shin

4/11/202521 min read

The Egyptian Empire stands as one of history's most remarkable civilizations, spanning over three millennia from approximately 3100 BCE to 30 BCE. Known for its monumental architecture, sophisticated religious practices, and groundbreaking contributions to mathematics, medicine, and astronomy, ancient Egypt continues to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike. This article explores the development, peak, and enduring legacy of this extraordinary civilization that flourished along the Nile River.

The Foundation of Ancient Egypt

The unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under King Narmer (also known as Menes) around 3100 BCE marked the birth of the Egyptian state. This pivotal moment established the framework for one of history's longest-lasting empires. The Nile River served as the lifeblood of the civilization, providing fertile soil through annual flooding and creating an agricultural surplus that supported a complex society.

Early Egyptian rulers developed sophisticated administrative systems to govern their expanding territory. The centralized government collected taxes, administered justice, and organized massive building projects. This period saw the establishment of hieroglyphic writing, which facilitated record-keeping and allowed for the preservation of Egyptian knowledge, culture, and history.

The Foundation of Ancient Egypt

The unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under King Narmer (also known as Menes) around 3100 BCE marked the birth of the Egyptian state. This pivotal moment established the framework for one of history's longest-lasting empires. The Nile River served as the lifeblood of the civilization, providing fertile soil through annual flooding and creating an agricultural surplus that supported a complex society.

Early Egyptian rulers developed sophisticated administrative systems to govern their expanding territory. The centralized government collected taxes, administered justice, and organized massive building projects. This period saw the establishment of hieroglyphic writing, which facilitated record-keeping and allowed for the preservation of Egyptian knowledge, culture, and history.

Predynastic Period and Early Development

Before unification, Egypt consisted of separate settlements along the Nile that gradually formed into two distinct kingdoms: Upper Egypt (the southern, upstream region) and Lower Egypt (the northern delta region). Archaeological evidence from sites like Nabta Playa and Hierakonpolis reveals increasingly complex social structures and early religious practices dating back to 6000-5000 BCE.

The predynastic period (c. 5500-3100 BCE) saw the development of distinctive pottery styles, ceremonial objects, and early attempts at pictographic writing. Communities established trade networks and began to develop specialized crafts. Religious beliefs centered around nature deities and ancestral worship laid the groundwork for the elaborate pantheon that would later emerge.

The Old Kingdom: Age of Pyramids

The Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BCE) represents the first peak of Egyptian civilization. During this period, Egypt achieved remarkable stability and prosperity under the rule of powerful pharaohs who were considered divine. The most enduring symbols of this era are the pyramids, which served as tombs for pharaohs and demonstrations of Egypt's organizational capabilities and engineering prowess.

The Great Pyramid of Giza, built for Pharaoh Khufu around 2560 BCE, remains one of the most impressive architectural achievements in human history. Standing at 481 feet tall and containing approximately 2.3 million stone blocks weighing an average of 2.5 tons each, this structure exemplifies the extraordinary technical knowledge and administrative efficiency of ancient Egypt.

Engineering and Construction Techniques

The construction of pyramids represented unprecedented feats of engineering. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that while slaves may have participated in construction, most workers were seasonal farmers who worked during the Nile's annual flood when agricultural work was impossible. These workers were organized into specialized teams with specific responsibilities.

Engineers used simple but ingenious tools, including copper chisels, wooden mallets, and dolerite pounders, to shape stones. They employed ramps, levers, and sledges to move massive blocks. The precision of the Great Pyramid is remarkable—the base is level within just 2.1 cm, and the sides are oriented to the cardinal directions with extraordinary accuracy.

Pyramid construction evolved significantly over time. Early step pyramids like Djoser's at Saqqara (designed by the architect Imhotep) gave way to true pyramids with smooth sides. Later pyramids incorporated complex internal chambers, corridors, and anti-theft devices. The knowledge required for these constructions encompassed geometry, astronomy, logistics, and materials science.

The First Intermediate Period: Disruption and Adaptation

Following the collapse of the Old Kingdom around 2181 BCE, Egypt entered a period of political fragmentation known as the First Intermediate Period. Central authority weakened as provincial governors (nomarchs) asserted independence, resulting in competing dynasties ruling from different centers. Climate change and lower Nile flooding may have contributed to this instability.

Despite political disunity, this period saw important cultural developments. Art became more diverse as regional styles flourished. Literature explored new themes, including texts that questioned traditional values and authority. Social mobility increased, with local officials rising in prominence. These changes laid the groundwork for the cultural flowering of the subsequent Middle Kingdom.

The Middle Kingdom: Cultural Renaissance

Following the decentralization of the First Intermediate Period, Egypt experienced a cultural renaissance during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE). This era saw the reunification of Egypt under the Theban rulers and a revival of art, literature, and architecture.

The Middle Kingdom is often described as the classical period of Egyptian culture. Literature flourished, producing works like "The Tale of Sinuhe" and "The Instruction of Amenemhat." Artistic conventions became more naturalistic, and religious concepts evolved, with Osiris gaining prominence as god of the afterlife. The period also saw expanded trade networks with neighboring regions, including Nubia, the Levant, and Crete.

Literary and Artistic Innovations

Middle Kingdom literature represents the pinnacle of ancient Egyptian literary achievement. "The Tale of Sinuhe," a sophisticated narrative combining adventure, political commentary, and psychological insight, follows an official who flees Egypt after the assassination of Pharaoh Amenemhat I and eventually returns from exile. "The Dialogue of a Man with His Ba" explores existential questions about life and death, while wisdom texts like "The Instruction of Ptahhotep" offer practical and ethical guidance.

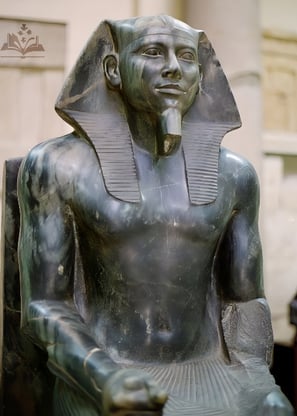

Artists of this period moved away from the idealized forms of the Old Kingdom toward more realistic representations. Sculptures featured more individualized facial features and natural body proportions. The royal portraits of Senwosret III and Amenemhat III are particularly notable for their depiction of careworn, mature faces—perhaps reflecting a new concept of kingship that emphasized the pharaoh's burden of responsibility.

Foreign Relations and Trade Expansion

The Middle Kingdom saw strategic expansion into Lower Nubia, with a series of massive fortresses constructed to secure Egypt's southern frontier and control trade routes. Archaeological evidence from these fortresses at sites like Buhen and Mirgissa reveals sophisticated military architecture, including moats, drawbridges, and massive mudbrick walls.

Trade connections expanded dramatically. Egyptian traders ventured to Punt (possibly modern Somalia or Yemen) for incense, gold, and exotic animals. Relations with Levantine cities brought cedar wood, oils, and wine. Minoan pottery from Crete appears in Egyptian contexts, while Egyptian artifacts have been found throughout the eastern Mediterranean, indicating extensive commercial networks.

The Second Intermediate Period and the Hyksos

Around 1650 BCE, Egypt again experienced political fragmentation. The most significant development of this period was the rise of the Hyksos, foreign rulers of West Asian origin who established a dynasty in the northeastern Delta. Traditionally portrayed as invaders, modern scholarship suggests they gradually gained power through immigration and political maneuvering.

The Hyksos introduced important technological innovations to Egypt, including the composite bow, improved bronze-working techniques, the horse and chariot, and new musical instruments. They adopted Egyptian culture and ruled as traditional pharaohs. Their presence ultimately prompted the Theban dynasty to develop military capabilities that would fuel the imperial expansion of the subsequent New Kingdom.

The New Kingdom: Imperial Expansion

The New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE) represented the zenith of Egyptian power and influence. Following the expulsion of the Hyksos rulers, Egypt transformed from a regional kingdom into a true empire with extensive territories and diplomatic connections across the ancient Near East.

Under ambitious pharaohs like Thutmose III, often called "Egypt's Napoleon," the empire expanded its boundaries through military campaigns into Syria-Palestine and Nubia. At its height, Egyptian influence extended from modern-day Sudan to the Euphrates River in Syria. The wealth accumulated through conquest and trade funded magnificent construction projects, including the temples at Karnak and Luxor.

This period also produced some of Egypt's most famous rulers, including:

Hatshepsut, one of history's most successful female pharaohs, who ruled for approximately 22 years and sponsored ambitious building projects

Akhenaten, who attempted to revolutionize Egyptian religion by promoting the worship of the Aten (sun disk)

Tutankhamun, whose relatively minor reign gained posthumous fame through the 1922 discovery of his nearly intact tomb

Ramesses II, who ruled for 67 years and constructed numerous monuments across Egypt

Military Organization and Imperial Strategy

The New Kingdom military represented a professional fighting force unlike anything seen in earlier periods. Standing armies replaced the previous system of conscription during conflicts. Professional soldiers received land grants and formed a distinct social class. The chariot corps, consisting of nobility, formed an elite branch that revolutionized battlefield tactics.

Egyptian imperial strategy focused on controlling key trade routes and natural resources while establishing buffer zones against potential rivals. Fortresses and administrative centers secured conquered territories. The empire employed a sophisticated system of vassal states in Syria-Palestine, where local rulers pledged loyalty to Egypt while maintaining some autonomy. Annual tribute and hostage-taking (where foreign princes were raised at the Egyptian court) helped maintain control.

Diplomatic Relations: The Amarna Letters

The Amarna Letters, a cache of diplomatic correspondence discovered at Akhenaten's capital city, provide unprecedented insight into international relations during the Late Bronze Age. Written primarily in Akkadian (the diplomatic language of the era), these clay tablets document communication between Egypt and other great powers, including Babylon, Assyria, Mitanni, and the Hittites.

The correspondence reveals a complex world of diplomatic marriages, gift exchange, trade negotiations, and occasional conflicts. Great kings addressed each other as "brothers," while smaller states acknowledged Egyptian supremacy. These letters demonstrate Egypt's central role in the first documented international system, sometimes called the "Club of Great Powers."

Akhenaten and Religious Revolution

Perhaps the most dramatic episode in Egyptian religious history occurred during the reign of Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten ("effective for the Aten") and initiated a radical religious reform. He elevated the Aten, previously a minor aspect of the sun god, to supreme deity while suppressing traditional cults, particularly that of Amun-Ra.

Akhenaten established a new capital city, Akhetaten (modern Amarna), dedicated to the Aten. Art during this period underwent dramatic transformation, featuring elongated, almost expressionistic depictions of the royal family. Religious texts emphasized the Aten as a universal deity who created and sustained all life, with the king serving as sole intermediary between humanity and the divine.

After Akhenaten's death, traditional religion was quickly restored under Tutankhamun and subsequent rulers. While once viewed as an early monotheist, scholars now understand Akhenaten's religious policy as more complex—an attempt to centralize religious power with the king rather than create a truly monotheistic faith.

The Ramesside Period: Maintaining Empire

The latter part of the New Kingdom, dominated by the pharaohs named Ramesses (particularly Ramesses II), represented Egypt's last period of imperial greatness. These rulers faced significant challenges from the rising Hittite Empire and the mysterious "Sea Peoples," who destabilized the entire eastern Mediterranean.

Ramesses II fought the Hittites to a standstill at the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE), commemorated in monumental inscriptions throughout Egypt. Following this indecisive engagement, he concluded history's first known peace treaty, establishing a lasting peace with the Hittites that included mutual defense provisions and extradition agreements.

The reign of Ramesses II marked an extraordinary building campaign. His mortuary temple, the Ramesseum; his Abu Simbel temples; and additions to nearly every major temple in Egypt demonstrated both his long reign and determination to leave a permanent mark on the Egyptian landscape. His construction of Pi-Ramesses in the Delta created a magnificent new capital city strategically positioned for Asian campaigns.

Administration and Society

The Egyptian Empire developed sophisticated administrative systems that enabled effective governance across vast territories. At the apex stood the pharaoh, considered a living god who maintained cosmic order (ma'at). Below the pharaoh were viziers, high priests, and nobles who supervised a complex bureaucracy of scribes, tax collectors, and local officials.

Egyptian society was hierarchical but not rigid. Social mobility was possible through education, particularly for scribes who mastered hieroglyphic writing. Women in ancient Egypt enjoyed more rights and opportunities than their counterparts in many other ancient societies, with the ability to own property, engage in business, and pursue legal actions.

Legal System and Justice

The Egyptian legal system operated on principles designed to maintain ma'at (cosmic order and justice). No comprehensive law code has survived, but legal documents reveal consistent application of precedent and principle. Courts operated at local, regional, and royal levels, with the pharaoh serving as the ultimate authority.

Legal proceedings emphasized evidence and testimony rather than ordeal or divine judgment. Witnesses swore oaths invoking the gods, and documents were sealed and witnessed to ensure authenticity. Punishment could be severe, including beatings, forced labor, mutilation, exile, or execution, but Egypt's justice system was generally more focused on restitution than retribution.

Women had significant legal rights, including the ability to bring cases to court independently, own and transfer property, and make contracts. Marriage was a civil arrangement rather than a religious ceremony, typically accompanied by a contract specifying property rights and divorce terms. While men could have multiple wives if they could afford them, monogamy was the most common practice.

Daily Life and Social Structure

Archaeological evidence from settlements like Deir el-Medina (a village housing workers who built royal tombs) provides rich insight into everyday Egyptian life. Houses typically featured multiple rooms arranged around a central hall, with roof terraces for outdoor activities during cooler evening hours. Furniture included beds, chairs, tables, and storage chests.

Diet varied by social class but generally centered around bread, beer, vegetables, and fruit, supplemented with fish, fowl, and occasionally red meat for wealthier citizens. Clothing was primarily linen, with complexity and quality indicating social status. Hygiene was emphasized, with evidence of cosmetics, perfumes, and regular bathing.

Families formed the core social unit, with extended households common. Children were highly valued, and evidence suggests emotional bonds between family members were strong. Education was primarily vocational, with sons typically following their fathers' professions. Literacy was limited to perhaps 1-3% of the population, primarily scribes, priests, and administrators.

Economic Foundations

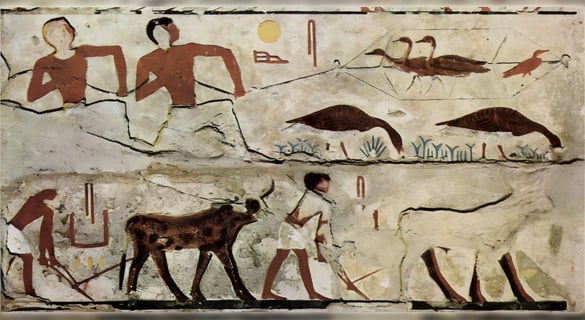

Agriculture formed the backbone of Egypt's economy, with the annual flooding of the Nile creating extremely fertile soil. Farmers grew wheat, barley, flax, and various fruits and vegetables. Surplus production supported specialized craftspeople, priests, officials, and soldiers.

Trade networks extended throughout the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and Africa. Egypt exported grain, papyrus, linen, gold, and manufactured goods while importing timber, oils, spices, and luxury items. The government carefully regulated commerce, with officials monitoring transactions and collecting taxes.

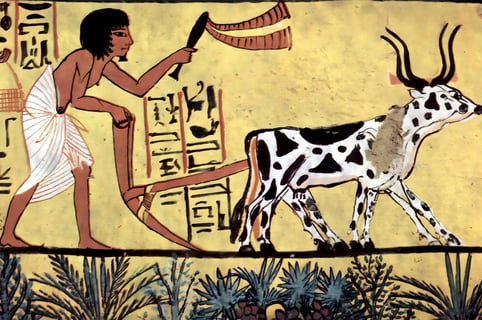

Agricultural Techniques and Land Management

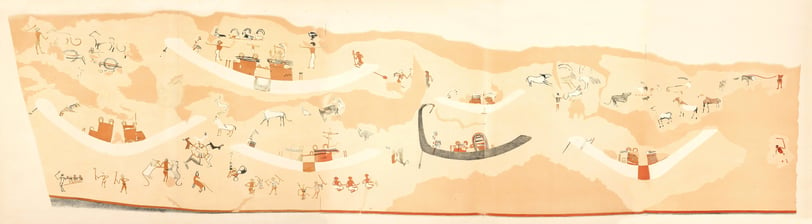

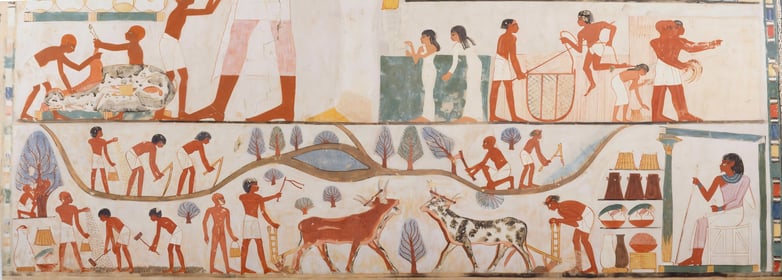

The distinctive Egyptian agricultural system relied on basin irrigation. During the annual Nile flood (mid-July to October), water was channeled into enclosed fields through a network of canals and dikes. When the waters receded, they left behind nutrient-rich silt perfect for planting. This system required minimal irrigation during the growing season but demanded a coordinated community effort to maintain canals and dikes.

Land ownership evolved over time. During the Old Kingdom, much land belonged directly to the crown or temple estates. By the New Kingdom, a more complex system had emerged with royal land, temple land, private estates, and communally managed village land. Farmers typically worked as tenants rather than owners, paying significant portions of their harvest as rent and taxes.

Agricultural innovation included the shaduf (a counterweighted lever for raising water), animal-drawn plows, and sophisticated crop rotation. Farmers cultivated two and sometimes three crops annually. Major grains included emmer wheat and barley, while flax provided material for linen. Vegetables included onions, garlic, lettuce, cucumbers, and melons. Fruit trees included date palms, figs, and pomegranates.

Manufacturing and Production

Egyptian craftspeople achieved extraordinary skill levels across numerous specialized fields. Textile production, particularly linen, represented a major industry employing both men (typically weaving) and women (typically spinning). Stone-working reached remarkable heights, with artisans using copper and bronze tools to shape everything from monumental sculptures to intricate jewelry.

Metalworking evolved significantly over time. Early copper working gave way to bronze (copper-tin alloy) during the Middle Kingdom. Gold working showed particular sophistication, with techniques including casting, hammering, chasing, granulation, and cloisonné. Egyptian faience, a quartz-based ceramic with vibrant blue-green glaze, provided an affordable alternative to precious stones.

Production was organized through both state workshops and private enterprises. Royal workshops produced luxury goods for the elite and items for international diplomatic exchange. Temple workshops created ritual equipment and statuary. Independent workshops served local markets with everyday items. Craftspeople often formed hereditary specializations, with skills passed from parent to child.

International Trade and Resources

Egypt's natural resources included abundant building stone (limestone, sandstone, and granite), gold mines in the Eastern Desert and Nubia, copper and turquoise mines in the Sinai, and agricultural abundance from the Nile Valley. However, Egypt lacked essential materials, including silver, tin (necessary for bronze), cedar wood, and certain luxury items.

Trade expeditions ventured to distant regions to acquire these materials. Sea voyages to Punt brought incense, gold, ebony, and exotic animals. Land routes to the Levant secured cedar wood, olive oil, and wine. Nubian campaigns ensured access to gold, ebony, ivory, and exotic animal products. By the New Kingdom, Egypt had established trade connections throughout the Mediterranean, with archaeological evidence of Egyptian goods found as far as Crete, Cyprus, and mainland Greece.

Intellectual and Cultural Achievements

Ancient Egyptians made remarkable intellectual contributions across multiple fields:

Mathematics and Astronomy

Egyptian mathematicians developed practical systems for land measurement, taxation, and architectural planning. They understood the concepts of fractions and geometry, applying these principles to construction and astronomy. Egyptian astronomers meticulously tracked celestial movements, creating a 365-day calendar that closely approximated the solar year.

The Moscow and Rhind Mathematical Papyri demonstrate sophisticated mathematical knowledge. Egyptians used a decimal system and had specific symbols for powers of ten. They could solve linear equations and calculate areas of triangles, rectangles, and circles (using an approximation of π as 3.16). Particularly notable was their facility with unit fractions (fractions with numerator 1), which formed the basis of their fractional system.

Astronomical observation served both practical and religious purposes. Egyptians identified stellar patterns and tracked their movements, particularly the annual reappearance of Sirius (which they called Sopdet), which coincided with the Nile flood. They divided night hours by observing the rising of specific star groups called decans. The resulting calendar had 12 months of 30 days plus five additional days, achieving remarkable accuracy without the concept of leap years.

Medicine

Egyptian physicians were among the ancient world's most advanced. Medical papyri like the Edwin Smith Papyrus (circa 1600 BCE) demonstrate sophisticated understanding of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Egyptian doctors performed surgeries, set broken bones, and prescribed medications derived from plants and minerals. Their medical knowledge was so respected that Greek physicians traveled to Egypt to study healing practices.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus reveals a surprisingly modern approach to trauma treatment, with systematic examination, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment recommendations for 48 types of injuries. The Ebers Papyrus contains over 700 prescriptions for various ailments, combining empirical treatments with magical elements. Egyptian doctors recognized the importance of pulse in diagnosis, understood the heart's role in blood circulation, and developed specialized practitioners for different medical fields.

Egyptian pharmacology utilized hundreds of substances from plant, animal, and mineral sources. Common treatments included honey (recognized for antibacterial properties), willow bark (containing salicylic acid, similar to aspirin), and various minerals. Surgical procedures included setting fractures, suturing wounds, and even brain surgery, as evidenced by skulls showing signs of trepanation with subsequent healing.

Art and Architecture

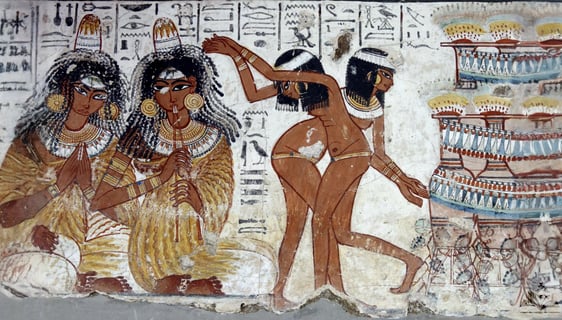

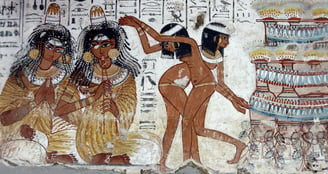

Egyptian artistic conventions remained remarkably consistent for thousands of years, featuring distinctive representations of the human form with the head in profile but the eye and shoulders facing forward. Temple and tomb paintings depicted daily life, religious ceremonies, and scenes from the afterlife with vibrant colors and precise detail.

Architecture reached extraordinary heights with temples, pyramids, and monuments designed to last "for millions of years." Buildings incorporated precise astronomical alignments and sophisticated understanding of structural engineering. The distinctive Egyptian architectural elements—massive pylons, hypostyle halls, and obelisks—influenced architectural styles throughout the Mediterranean world.

Artistic Principles and Development

Egyptian art adhered to formal principles that maintained consistent style over millennia while allowing subtle evolution. The "canon of proportions" used a grid system to ensure human figures maintained proper proportions. Artists emphasized clarity and completeness rather than perspective, showing objects and people from their most characteristic angle.

Despite stylistic conventions, Egyptian art underwent notable developments. Old Kingdom art emphasized idealized, timeless representations. Middle Kingdom works introduced more naturalistic elements and individual characteristics. New Kingdom art, particularly during the Amarna period, briefly experimented with unprecedented naturalism before returning to more traditional forms.

Color held symbolic significance, with specific colors associated with particular concepts: blue and green with regeneration, red with both danger and vitality, yellow with eternity, white with purity, and black with fertility and rebirth. Painters used mineral-based pigments that have retained remarkable vibrancy for thousands of years.

Architectural Innovation

Temple architecture evolved from simple shrines to massive complexes. The typical New Kingdom temple featured an entrance pylon (monumental gateway), open courtyard, hypostyle hall (forest of columns), and inner sanctuary with decreasing light levels symbolizing the transition from earthly to divine realms.

Structural innovations included the development of columns inspired by natural forms (papyrus, lotus, palm), sophisticated understanding of weight distribution, and precise astronomical alignments. The temples of Karnak and Luxor represent the culmination of these techniques, with the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak containing 134 massive columns, some reaching over 20 meters tall.

Residential architecture showed practical adaptation to climate. Houses featured thick walls for insulation, small windows placed high to reduce heat while providing ventilation, and roof terraces for outdoor living during cooler evening hours. Urban planning is evident at sites like Amarna and Deir el-Medina, with gridded streets and specialized districts for different activities.

Religion and Afterlife

Religion permeated every aspect of Egyptian life. The complex pantheon included hundreds of deities associated with natural forces, human activities, and cosmic phenomena. Major gods included Amun-Ra (sun god), Osiris (god of the afterlife), Isis (goddess of motherhood and magic), and Horus (god of kingship).

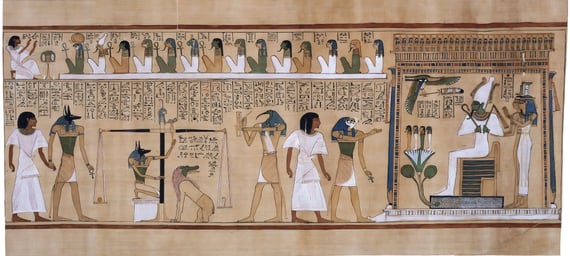

The Egyptian conception of the afterlife was elaborate and optimistic. They believed that through proper preservation of the body (mummification) and appropriate rituals, the deceased could enjoy eternal life. Funerary texts like the Book of the Dead provided instructions for navigating the underworld and passing judgment before Osiris.

Religious Concepts and Practices

Egyptian religion balanced seemingly contradictory elements: polytheism alongside tendencies toward unifying deities, local cults alongside state religion, and formal temple worship alongside personal piety. Gods could merge, split, or transform, with deities often grouped in triads or enneads (groups of nine).

Cosmological beliefs centered on maintaining ma'at (cosmic order) against the forces of chaos. Creation myths, though varying regionally, typically described the emergence of a primordial mound from chaotic waters, with a creator deity (often Atum or Ptah) initiating existence through thought and speech.

Religious practice included daily temple rituals performed by priests who maintained divine cult statues through washing, clothing, and feeding ceremonies. Seasonal festivals involved processions where cult statues visited other temples or appeared before the public. Evidence from the New Kingdom onward suggests increasing personal religious practice, with individuals seeking direct divine intervention through prayer and votive offerings.

Mortuary Beliefs and Practices

Egyptian concepts of the afterlife evolved significantly over time while maintaining core principles. The deceased was thought to combine several spiritual elements beyond the physical body, including the ka (life force), ba (personality), and akh (transformed spirit). Proper mortuary rituals ensured these elements could reunite in the afterlife.

Mummification techniques developed to preserve the body as a dwelling place for the soul. The process, lasting approximately 70 days, involved organ removal (except the heart), desiccation using natron salt, application of preservative resins, and elaborate wrapping. Canopic jars preserved vital organs, while funerary masks provided an idealized face for the deceased's spirit to recognize.

Tomb development reflected changing concepts of the afterlife. Early simple pit graves gave way to mastabas (bench-shaped structures), pyramids, and eventually rock-cut tombs. Tomb walls featured scenes of daily life to magically provide sustenance, religious texts to assist the journey to the afterlife, and images of the deceased to serve as alternative homes for the spirit.

The judgment of the dead became increasingly important in Egyptian belief. The heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of ma'at, with Osiris presiding over the judgment. Those deemed worthy joined Osiris in the Field of Reeds, a perfected version of earthly life. Those found wanting faced consumption by Ammit, a fearsome hybrid creature.

Later Periods and Foreign Rule

Following the New Kingdom, Egypt entered a period of declining power and increasing foreign influence:

Third Intermediate Period and Late Period

During the Third Intermediate Period (1070-664 BCE), Egypt fragmented into competing power centers. Libyan-descended dynasties ruled in the Delta while priest-kings controlled Thebes in the south. Despite political division, cultural and religious traditions continued with remarkable consistency.

The Late Period (664-332 BCE) saw alternating periods of independence and foreign rule. The 26th Dynasty (Saite Period) achieved a cultural renaissance, consciously reviving artistic styles and religious practices from earlier periods. Persian rule under the 27th and 31st Dynasties brought Egypt into a vast empire extending from the Indus Valley to the Mediterranean.

Ptolemaic Dynasty

Alexander the Great's conquest in 332 BCE led to the establishment of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, a Macedonian Greek family that ruled Egypt for nearly 300 years. The Ptolemies adopted Egyptian religious practices and portrayed themselves as traditional pharaohs while maintaining Greek culture and administrative systems.

Alexandria, founded by Alexander, became the Mediterranean's preeminent cultural and intellectual center. The famous Library of Alexandria collected texts from throughout the known world, while the Museum (literally "shrine of the Muses") functioned as an early research institution where scholars studied mathematics, astronomy, geography, medicine, and literature.

The Ptolemaic period saw significant cultural synthesis between Greek and Egyptian traditions. Temple construction continued in traditional Egyptian style but often incorporated Greek architectural elements. The cult of Serapis, combining aspects of Osiris and Greek deities, represented a deliberate attempt to unify Greek and Egyptian religious practices. Cleopatra VII, the dynasty's final ruler, was the first Ptolemy to learn the Egyptian language.

Roman Egypt

Following Cleopatra's defeat by Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) in 30 BCE, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. As Rome's "breadbasket," Egypt's agricultural wealth was harnessed to feed the imperial capital. The emperor maintained tight control over Egypt, prohibiting senators from visiting without explicit permission.

Under Roman rule, Egypt's administrative system became increasingly complex and bureaucratic. The population faced heavy taxation and compulsory labor requirements. Social stratification intensified, with Roman citizens at the top, followed by Greek citizens and native Egyptians at the bottom. Despite these changes, traditional religious practices continued at major temple complexes like Philae, Dendera, and Kom Ombo.

During this period, Egypt became an early center of Christianity. According to tradition, Mark the Evangelist established the Coptic Church in Alexandria during the 1st century CE. By the late Roman period, Christianity had spread widely, sometimes coming into conflict with traditional practices. The last known hieroglyphic inscription dates to 394 CE, while the Temple of Isis at Philae continued functioning until Emperor Justinian closed it in the 6th century CE.

Rediscovery and Modern Understanding

Interest in ancient Egypt never completely disappeared but intensified during the Renaissance as European travelers and scholars encountered Egyptian monuments. Napoleon's Egyptian expedition (1798-1801) included scientific researchers who documented monuments and artifacts, publishing their findings in the monumental "Description de l'Égypte."

The decipherment of hieroglyphics by Jean-François Champollion using the Rosetta Stone in 1822 revolutionized Egyptology by providing access to the civilization's written record. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw extensive archaeological excavation, sometimes conducted with limited scientific rigor. Howard Carter's discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922 captured global imagination and brought unprecedented public attention to ancient Egypt.

Modern Egyptology employs increasingly sophisticated techniques, including satellite imaging, ground-penetrating radar, DNA analysis, and computer modeling. These approaches have revealed new monuments, clarified chronology, provided insight into health and disease patterns, and enhanced understanding of construction techniques.

Enduring Impact and Legacy

The legacy of ancient Egypt extends far beyond its historical timeline:

Egyptian architectural principles influenced Greek, Roman, and later Western building traditions

Egyptian religious concepts regarding immortality and divine judgment influenced developing monotheistic religions

Egyptian mathematical and astronomical knowledge contributed to the foundation of Western science

Egyptian artistic conventions have inspired artists throughout history

Hieroglyphic writing, deciphered in the 19th century through the Rosetta Stone, opened a window into one of humanity's earliest literary traditions

Cultural Transmission and Influence

Ancient Egyptian concepts and practices influenced neighboring civilizations during antiquity. The Kushite civilization of Nubia adopted Egyptian religious practices, hieroglyphic writing, and architectural forms, even ruling Egypt during the 25th Dynasty. Hebrew scriptures contain numerous references to Egypt, while Greek philosophers, including Pythagoras and Plato, reportedly studied with Egyptian priests.

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, Egyptian religious concepts spread throughout the Mediterranean world. The cults of Isis and Serapis gained popularity across the Roman Empire, with temples established as far away as Britain. Egyptian concepts of the afterlife influenced mystery religions that promised personal salvation and transcendence.

Modern Reception and Representation

Egypt has occupied a special place in Western imagination since antiquity. Roman fascination with Egyptian culture manifested in obelisks transported to Rome and Egyptian-themed artworks at Pompeii and Herculaneum. The Renaissance rediscovered classical texts describing Egypt, stimulating new interest in its monuments and wisdom traditions.

Napoleon's Egyptian campaign triggered "Egyptomania" in European and American art, architecture, and design during the 19th century. Egyptian motifs appeared in furniture, jewelry, and decorative arts, while Egyptian revival architecture influenced public buildings, cemeteries, and monuments. The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb inspired Art Deco designs and further popularized Egyptian aesthetics.

In contemporary culture, ancient Egypt remains a powerful source of fascination, appearing in films, literature, video games, and popular media. While these representations often incorporate fantasy elements and misconceptions, they reflect the enduring appeal of Egypt's visual distinctiveness and mysterious aura.

Scientific and Technological Legacy

Egyptian innovations in mathematics, engineering, medicine, and astronomy laid important groundwork for later scientific development. Their practical approach to mathematics, emphasizing problem-solving over theoretical proofs, provided useful techniques adopted by Greek mathematicians. Their solar calendar, with minor modifications, evolved into the Julian and eventually Gregorian calendars used today.

Medical knowledge from ancient Egypt influenced Greek medicine through figures like Hippocrates and later Arab physicians. Egyptian surgical techniques, pharmacological knowledge, and anatomical observations provided foundations for later medical traditions. Their architectural and engineering achievements demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of mathematics, materials science, and project management.

The Egyptian Empire represents one of humanity's most impressive achievements—a civilization that maintained remarkable cultural continuity for over 3,000 years while creating enduring monuments, sophisticated religious concepts, and pioneering intellectual advances. Modern archaeology continues to uncover new dimensions of this extraordinary civilization, enhancing our understanding of its complexity and achievements.

The timeless allure of ancient Egypt—its monumental architecture, artistic brilliance, spiritual depth, and intellectual sophistication—continues to inspire wonder and respect. As we study this remarkable civilization, we gain valuable insights into the foundations of human society and the remarkable heights that concentrated human effort can achieve.

Subscribe to our newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚